All About Dreams

Dreams are an essential part of the human experience. They’re universal; as near as science can show (without literally reading people’s minds) every person dreams when they sleep.

So why do we dream?

It’s been a popular question for thousands of years—possibly since before the dawn of civilization. Some of our earliest recorded texts relate to the interpretation of dreams and visions; how what we see in our sleep might relate to the past, present, and what is yet to come.

Only recently, though, has scientific thought advanced to the point of in-depth analysis as to why we dream. It’s no easy question: evidence and answers come from a variety of disciplines across the sciences and humanities, including philosophy, psychology, neuroscience, and biology. It’s become one of the most highly contested (and fascinating) debates in modern science.

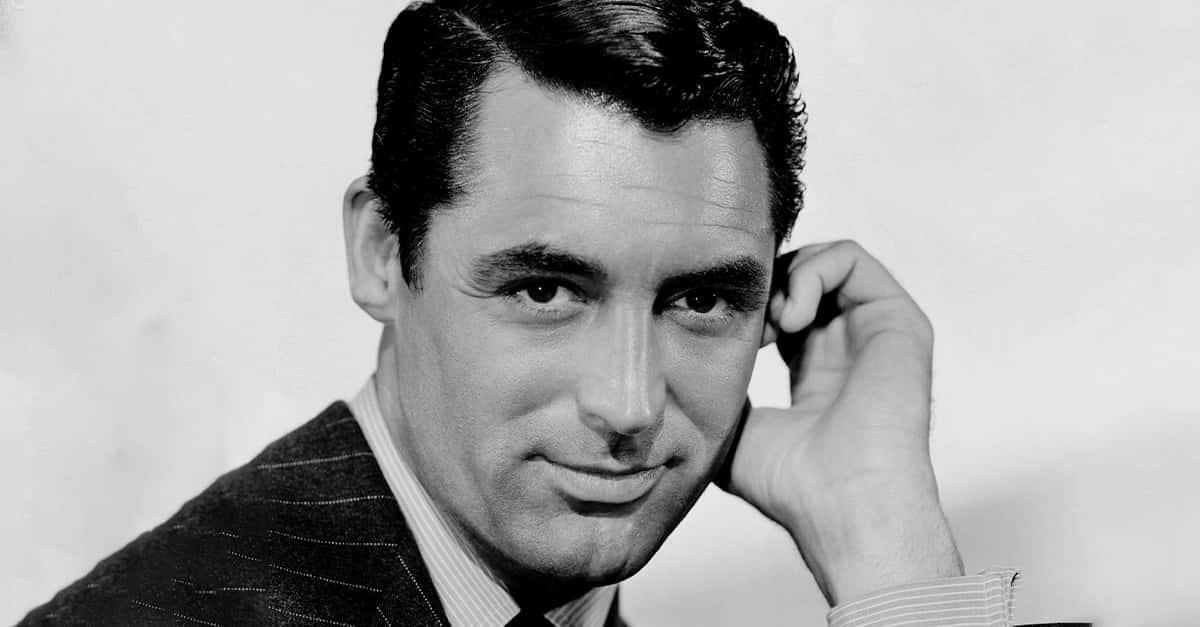

Shutterstock

Shutterstock

There are, broadly speaking, two major camps:

There are those who believe that dreaming is simply a side-effect of bodily processes unable to slow down. To proponents of this theory, dreams are a consequence of other, more essential nervous functions, which inadvertently lead to hallucinations when sleeping. This would mean that dreams have no deep meaning or purpose—just a consequence of our large and complex brains.

Others, however, propose that dreaming is itself an essential function. Researchers of this opinion tend to argue that dreams, as much as sleep itself, serve a role in maintaining our physical and mental health. These claimants believe that we could no more live without dreaming than we could live without food, water, or air.

It should be noted, as well, that the study of dreaming is undertaken differently depending on the discipline of those conducting the research. Neuroscientists, for example, seek to understand the underlying physical causes of dreaming, and how the experience of a dream might impact the brain and body of their subjects. Psychoanalysts, meanwhile, will usually concern themselves with the psychological importance of dreaming—how they reflect our conceptions of self, or how they help us to learn and adjust.

How Sleep Works

There are several different interpretations of the different phases of sleep. What is universally understood, however, is that sleep can be divided into REM (Rapid Eye Movement) and Non-REM sleep. Chances are, REM is the one you’ve heard about. The REM cycles makes up about 25% of your night’s sleep—it usually occurs around 90 minutes after you first fall asleep, and occurs several more times throughout the night as you pass through other sleep stages.

What we know without a doubt is that the REM stage is when dreaming occurs. During REM, signals are sent by the body’s nervous system to your spine, causing a form of partial paralysis. Regions of the brain responsible for learning, emotion, and memory then experience a surge of activity. The exact process by which this causes us to experience vivid hallucinations while sleeping (which we call dreams) is still not known.

Shutterstock

Shutterstock

Dreaming And Memory

While scientists have yet to identify the exact cause of our dreams, there is a growing consensus that the purpose our dreams serve has much to do with the way we process memories.

REM sleep (when dreaming occurs) triggers the parts of our brain responsible for learning and memory recall. Studies have repeatedly shown that those who go for a period of time without REM sleep struggle to accurately store new information in a way that allows for later recall.

As teams of investigators develop this theory, some have actually proposed that fragments of a person’s memories can be identified in the contents of a person’s dreams.

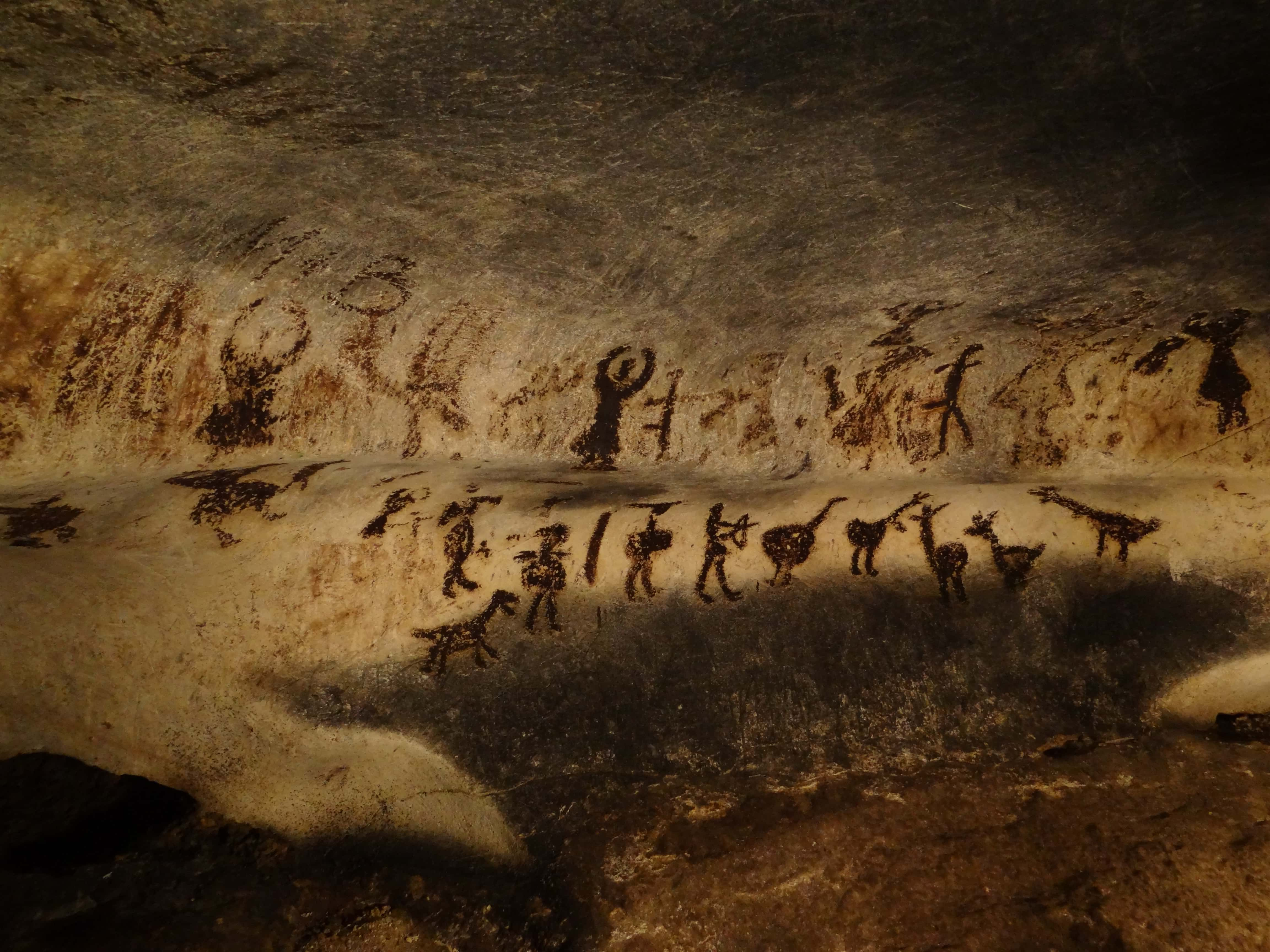

In this vein, Professor Sue Llewellyn at the University of Manchester in England has proposed that the act of dreaming serves as a type of memory boosting exercise. According to Llewellyn, dreams enhance memory recall through methods similar to those used by ancient peoples, before writing was commonplace.

The oral traditions of many ancient civilizations relied on a series of memorization techniques to pass down information between generations. These include visualization, narration, personal embodiment, and the making of strange associations between seemingly unrelated concepts. Professor Llewellyn proposes that these same techniques are used naturally during REM sleep to promote accurate information storage in the brain.

Shutterstock

Shutterstock

Did Dreams Help Us Survive?

As it turns out, dreams might be a form of practice.

Fantastic scenarios that involve fighting, or being chased, are near-universal dream experiences. The explanation may lie in the amygdala—your brain’s emotional response command center. When a person enters REM sleep, their amygdala fires on all cylinders—as though the brain is responding to a serious threat. It is this hyperactivity in the amygdala which could hold the secret to our nightmares.

Now, that hyperactivity could simply be random. A quirk of human evolution, maybe. Like the appendix. But some experts speculate that dreams, specifically nightmares, serve a far more dramatic purpose.

In the early days of our evolution, threats to human life were far more abundant. Predators, specifically, posed a legitimate risk to most human populations. These were the days when a bear attack, or encounter with rival tribes, were common. The ability to process these risk was incredibly important. Responding to a threat with a cool, calm, collected head might be the difference between life-and-death.

Dreams (more specifically, nightmares) could serve for those situations. A person who dreamed more often, and more vividly, may be better equipped to deal with genuine terror. In this theory, nightmares serve the same person as a flight-simulator for a pilot. If a first-time pilot experiences a blown engine mid-flight, they might panic and lose control. Whereas a pilot who has trained thousands of times for that exact scenario, in the controlled environment of simulation, should react with a level-head.

The theory is unproven. For now, the implications remain fascinating.

Shutterstock

Shutterstock

What Do Dreams Mean?

It could be the most asked question in human history: do my dreams mean something? If so, what?

How many hundreds of thousands have lain in bed, just recently asleep, and wondered? It’s an essential mystery of the human experience.

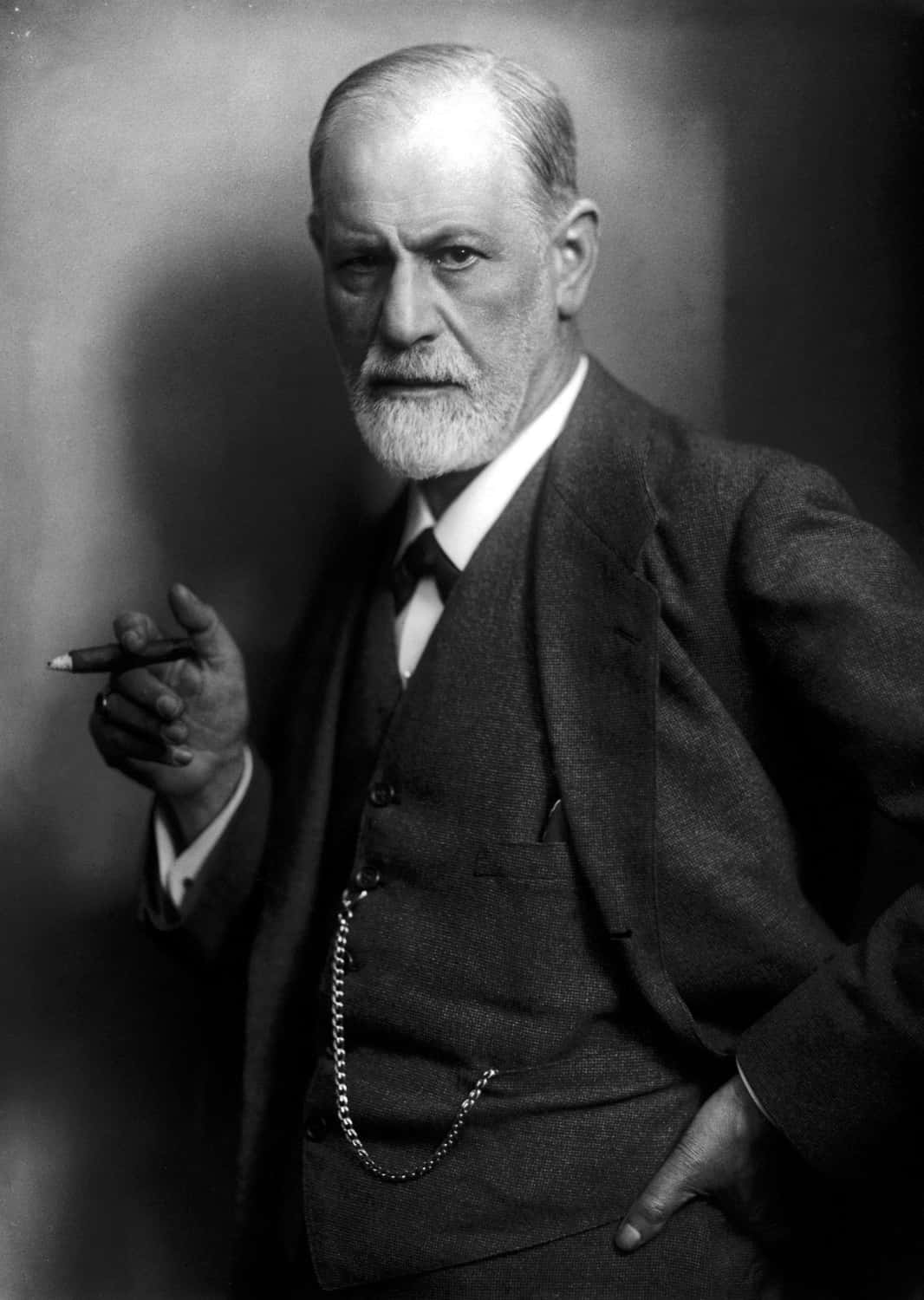

Today, the first name to come up when considering this question is Sigmund Freud. In his work, Freud argued that dreams are an essential channel into understanding one's inner thoughts. When examining the emotional lives of his patients, Freud used dreams as a guide. To him, the symbols and themes of a person's dreams reflected hidden thoughts and desires—hidden somewhere deep in the brain. As he said, “Dreams are the royal road to the unconscious.”

This line of thought has since come to dominate the cultural interpretation of dreams (at least in the Western world). In one study conducted on college students in the United States, India, and South Korea, researchers found that almost no participants believed their dreams were merely random. Instead, many shared a Freudian-esque notion that what they experienced in dreams reflected their innermost thoughts and desires.

That doesn't necessarily imply that a dream's "meaning" is supernatural, or tied to something outside the bounds of human physiology. In the words of G. William Domhoff, Professor of Psychology at the University of California:

“'Meaning' has to do with coherence and with systematic relations to other variables, and in that regard, dreams do have meaning. Furthermore, they are very 'revealing' of what is on our minds. We have shown that 75 to 100 dreams from a person give us a very good psychological portrait of that individual. Give us 1,000 dreams over a couple of decades and we can give you a profile of the person's mind that is almost as individualized and accurate as her or his fingerprints."

Wikimedia Commons Sigmund Freud

Wikimedia Commons Sigmund Freud

What About Lucid Dreaming?

Chances are you’ve heard some pretty marvelous things about lucid dreams. A quick online search turns up any number of fantastic claims. Some say they’ve built a long-term “mind palace” they’re able to visit and revisit every night, while sleeping, in their dreams. Some say lucid dreaming has changed their lives.

Is it a real phenomenon?

At a basic level, it doesn't take much for a dream to be lucid. If at any moment the dreamer is aware they are asleep and dreaming, the dream itself is lucid. Any moment of self-awareness is enough. As the Greek philosopher Aristotle once said, “often when one is asleep, there is something in consciousness which declares that what presents itself is but a dream.”

Often, though, when a person discusses lucid dreaming, what they’re referring to is the ability to influence the environment and outcome of the dream itself.

I dreamed I was a butterfly, flitting around in the sky; then I awoke. Now I wonder: Am I a man who dreamt of being a butterfly, or am I a butterfly dreaming that I am a man?—Zhuangzi

Shutterstock

Shutterstock

The Mysteries Of Our Brain

Our knowledge of the human brain is still very much a work in progress. Scientific understandings of consciousness, psychology, and neuroscience are in flux, as new discoveries and theories are released almost every day.

What this means for the study of dreaming is as of yet unclear.

Why do people dream? The question will undoubtedly continue to fascinate some of humanity's greatest minds. Billions will wonder. Scientists will study. Researchers will collaborate. Doctors and psychologists and thousands of others will wait with bated breath.

For now, it would seem current research suggests that our dreams play a role in memory, in self-identity, and in the processing of our daily experiences. It's a critical aspect of our sleep. Why exactly that is, and how exactly it occurs, will continue to be one of the most interesting questions in modern medicine. And then, of course, there's lucid dreaming.